The War on Drugs, Legalisation

The War on Drugs, Tea, Coca-Cola

Psychoactive Revolution

Historical View

Ten years ago, while killing time between ºMarlboro lights in a duty-free shop, I found myself wondering why I was surrounded by drugs. Marlboro cartons loomed to my left, Drambuie bottles to my right, Belgian chocolates behind me, Kenyan coffee straight ahead—everywhere I looked, I saw imported psychoactive products. How did these things get here? And why could “here” be anywhere—why did duty-free shops all seem to be stocked with the same merchandise? (Indeed, I can no longer recall which airport I was passing through.) Though I had long been interested in the history of narcotic drugs, this book grew out of a broader curiosity about psycho active commerce, a ubiquitous—and, I now believe, defining—feature of the modern world (Courtright, 2001)

Revolution

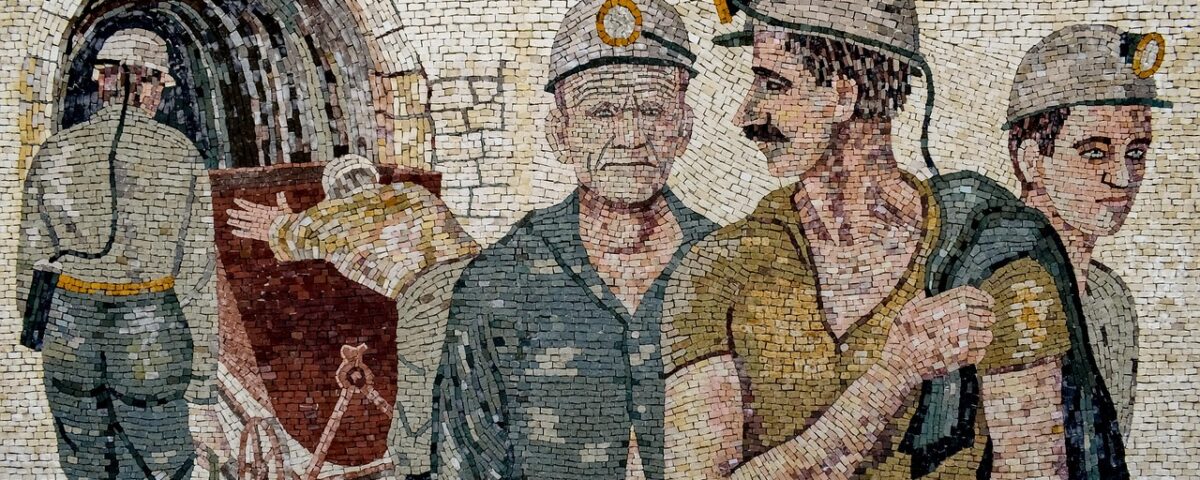

People everywhere have acquired progressively more, and more potent, means of altering their ordinary waking consciousness. One of the signal events of world history, this development had its roots in the transoceanic commerce and empire building of the early modern period—that is, the years from about 1500 to 1789.

Forces of Habit describes how early modern merchants, planters, and other imperial elites succeeded in bringing about the confluence of the world’s psychoactive resources and then explores why, despite enormous profits and tax revenues, their successors changed their minds and restricted or prohibited many—but not all—drugs.

The term “drugs” is an extremely problematic one, connoting such things as abuse and addiction. For all its baggage, the word has one great virtue. It is short. Indeed, one of the reasons its use persisted, over the objections of fended pharmacists, was that headline writers needed something pithier than “narcotic drugs.”

In this book I use “drugs” as a convenient and neutral term of reference for a long list of psychoactive substances, licit or illicit, mild or potent, deployed for medical and nonmedical purposes. Alcoholic and caffeinated beverages, cannabis, coca, cocaine, opium, morphine, and to bacco are all drugs in this sense, as are heroin, methamphetamine, and many other semisynthetic and synthetic substances. None is inherently evil. All can be abused. All are sources of proof.

#All have become, or at least have the potential to become, global commodities. This might not be apparent from a casual inspection of drug histories. Most scholarship deals with drugs or types of drugs in a particular set ting: tea in Japan, vodka in Russia, narcotics in America, and so on.

# Disease and drug exchanges have many close parallels. That imported alcohol, for example, acted as a deadly pathogen for indigenous peoples is more than a metaphor. But there are also important differences.

#McNeill’s story was largely one of tragic happenstance. Invisible germs spread by human contact had lethal but usually unintended consequences. The spread of drug cultivation and manufacturing, however, was anything but accidental. It depended on conscious human enterprise, and only secondarily on unconscious biological processes (McNeill, 1976).

These substances, once geographically confined, all entered the stream of global commerce, though at different times and from different places. Coffee, for example, spread from Ethiopia, where the bush was indigenous, to Arabia, and then throughout the Islamic lands and Christian Europe.

#Europeans took the taste and the beans to the Americas, which produced 70 percent of the world’s coffee crop by the late nineteenth century. European farmers and planters, employing indentured and slave labour, enjoyed great success cultivating drug crops in both hemi spheres.

Their collective efforts expanded world supply, drove down prices, and drew millions of less affluent purchasers into the market, democratizing drug consumption. Drugs typically began their careers as expensive and rerated medicines, touted for a variety of human and animal ailments.

Once their pleasurable and consciousness-altering proper ties became known, they escaped the therapeutic realm and entered that of popular consumption. As they did so, their political status changed. Widespread nonmedical use of spirits, tobacco, amphetamines, and other psycho active substances occasioned controversy, alarm, and official intervention.

#All large-scale societies differentiated in some way between the medical use and the nonmedical abuse of drugs, and eventually they made this distinction the moral and legal foundation for the international drug control system.

Such a system was necessary because drugs were at once dangerous and lucrative products. The opposite of “durable goods,” they were quickly consumed and had to be just as quickly replaced by those dependent on them. Regular users needed larger doses to experience the original effect, which meant that the volume of sales was likely to increase.

Inventions such as improved stills, hypodermic syringes, and blended cigarettes made for more efficient, speedier, and more profitable ways to get refined chemicals into consumers’ brains.

Competition sparked further innovation and widespread advertising, as manufacturers sought to cut their costs, increase market share, and enhance the appeal of their products. As drugs became cheaper and more seductive, they attracted millions of new users, generating profitable opportunities in enterprises ranging from addiction treatment to Zippo lighters.

Drug commerce and its externalities were manifestations of mature capitalism’s limbic turn, its increasing focus on pleasure and emotional gratification, as opposed to consumers’ material needs. Drug commerce, to paraphrase the anthropologist Robert Ardrey, ºnourished in a world in which the hungry psyche was replacing the hungry belly.

The third section, which concerns drugs and power, shows how psychoactive trade benefited mercantile and imperial elites in ways that went beyond ordinary commercial profits. These elites quickly discovered that they could use drugs to control manual labourers and exploit indigenes.

Opium, for instance, kept Chinese labourers in a state of debt and dependency. Alcohol in Duce native peoples to trade their furs, sell their captives into slavery, and negotiate away their lands. Early modern political elites found drugs to be dependable sources of revenue.

Though rulers were often initially hostile to novel drugs (tobacco struck them as an especially nasty foreign vice, provoking sanctions from royal denunciations to ritual executions), they bowed to the inevitable and imposed taxes or their equivalents, monopolies, on the expanding commerce. They prospered beyond their dreams.

By 1885 taxes on alcohol, tobacco, and tea accounted for close to half of the British government’s gross income. Drug taxation was the cornerstone of the modern state, and the chief financial prop of European colonial empires. Political elites do not ordinarily kill the geese that lay their golden eggs.

Yet, during the last hundred years, they have selectively abandoned a policy of taxed, legal commerce for one of greater restriction and prohibition, achieved by domestic legislation and international treaties (Courtright, 2001).

Wine

Viticulture, the selective cultivation of grape vines for making wine, exemplifies the global diffusion process. Viticulture probably originated in the mountainous region between the Black and Caspian seas, where Armenia is now located, sometime between 6000 and 4000 b.c.

Spirits

European ships carried new technologies as well as new plants. Among the most important of these was distilling. Known to the Greeks and Romans, preserved and advanced by the Arabs, distilling entered Europe via Salerno in the eleventh century. Printed books on distilling, which began appearing in the late fifteenth century, spread knowledge of the technique.